Discovering the Place, the Path, the Space of Intersubjectivity

Choosing to focus on the idea of intersubjectivity, the relation between people’s cognitive perspectives, particularly including Edith Stein’s idea of intersubjectivity based in empathy, I argue that there is an influential relationship between architecture and space, how we are affected by it, and how we perceive ourselves within it. Intersubjectivity considers the “experience of the world as available not only to oneself, but also to the other, there is a bridge between the personal and the shared, the self and the others.” This could not be more relevant when regarding art “works” in public spaces. As Shukaitis explains, “Stencil and graffiti art as well as street performance play an important role in breaking down the wall between artistic activity as separate or removed from daily life because these forms can be inscribed within the flow of people’s everyday experience.” We can consider affective composition in terms of this by the capacity it creates and how it somehow impels forms of self-organization.

This was directly seen by the facilitation of the self-actualization of a mob, through the work of the Infernal Noise Brigade. Their marching band, and the ways they subtly, yet radically managed to use artistic performance to undercut usual spaces, creating mobile and affective composition in the streets, allowing new relations and dissemination of data to emerge in the midst of overwhelming media influence, is powerful, affective and effective. Their mission, to dissolve all barriers between art and politics, participants and spectators, dream and action, is achieved through subliminal disruption, choosing noise as their medium. Leader Jennifer Whitney affirms, “During times of revolt there is a brilliant flash of direct truth, connecting internal desire with external reality and smashing the barriers between the two. In that instance, that dangerous moment of ultimate presence and clarity, we become alchemists, forging the future from the energy of spontaneous passionate imagining, and fueling it with infernal noise.”

Using a projector rather than noise, Wodiczko’s philosophy of art as a social contract is further indicative of this. In Exodus 90, he, as a nomadic artist, depicted Jerusalem as a monument to a nomad who “became a state, real estate, immobile.” Wodiczko used gentle ambiguity to convey both the politics of culture and the psychology of bureaucracy relating refugee camps and the subsidization of immigrant Soviet Jews on a nameless hotel, as the Tower of Babel. He connected the spiritual with the material, asking pertinent questions of identity, of immigrant culture. His work used architecture and space, affective composition by projecting a suitcase and passport juxtaposed with a hand holding a wooden staff. This work of the immigrant and the exodus profoundly resonated between the personal and the shared, the self and others, and one’s relation to and within it all.

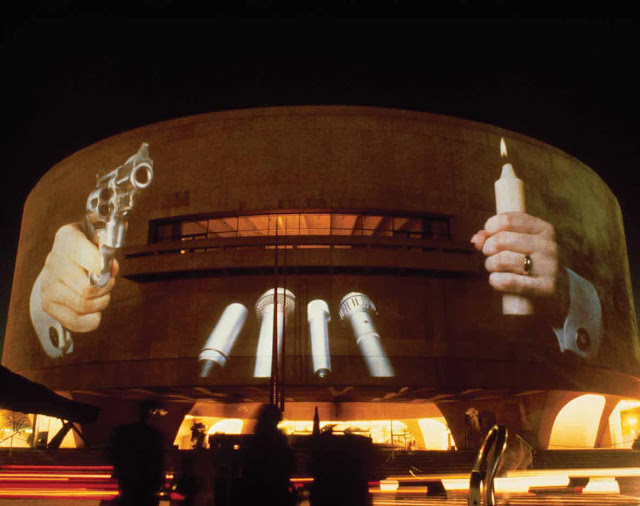

I unexpectedly related my newfound learning from the readings and film to my Walk 5 in Washington D.C. As I passed the Hirschhorn Museum on the National Mall, I recalled Wodiczko’s powerful projection on its walls the week before the 1988 U.S. Presidential election. His work comprised two hands embracing the museum, one hand pointing a gun, the other hand holding a lit candle, both representing George W. Bush’s contradictory campaign rhetoric, in favor of both the death penalty and against abortion. Microphones below the hands referenced media as “weapons” used in campaign battles. Wodiczko focused on social structures as a means to manipulate people, and also to the ever-increasing power of the media to disseminate preferred ideology.

As I walked past the Hirschhorn, in the midst of people protesting the Supreme Court overturning of Roe vs. Wade, I thought how powerful it would be to have with us all, the Infernal Noise Brigade, marching up the Mall, and a Wodiczko-like projection of a clothes hanger and a cross lighting up the Washington Monument.

Comments

Post a Comment